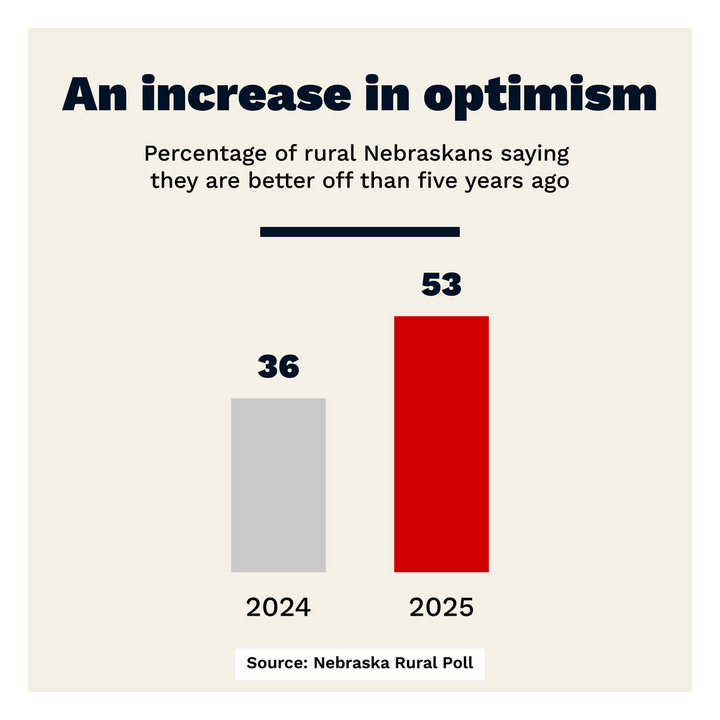

Over the past 30 years, the Nebraska Rural Poll has asked respondents about their current well-being, as well as their outlook on their future. This year, 53% of respondents believe they are better off than they were five years ago, up from 36% last year. This increase in optimism was matched with a sharp decrease in pessimism. This year, just 16% of rural Nebraskans surveyed believe they are worse off compared to five years ago, down from 33% last year.

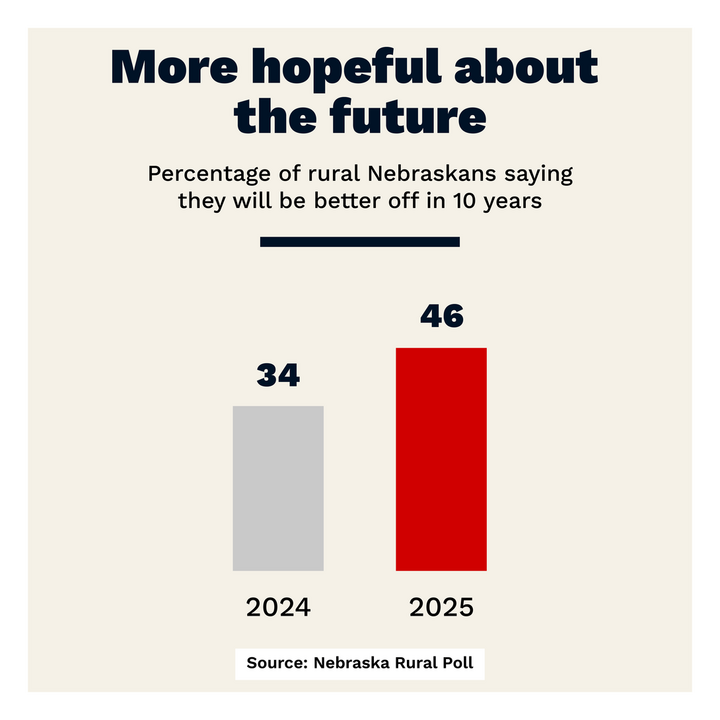

This same trend of increased optimism held when asked about the future, said Becky Vogt, poll manager. Forty-six percent of rural Nebraskans surveyed indicate they will be better off 10 years from now, up from 34% last year. The proportion of respondents stating they will be worse off in a decade declined slightly from last year (26% to 20%).

“The increase in optimism seems to be in spite of increased economic uncertainty, particularly in ag,” said Brad Lubben, associate professor of agricultural economics at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. “One explanation could be because we’re comparing 2025 to 2020, when we were in the early stages of COVID-19. Comparisons of pre- vs. post-COVID changes in attitude have previously been tied to increased pessimism, but thinking about now versus the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic may leave little comparison.”

Certain groups are more likely to be optimistic about their current situations, as well as about their futures, according to the poll. These include younger people, households with higher incomes, households with higher levels of education and people who have never married.

A possible explanation of the increased feelings of optimism is that rural Nebraskans expressed more satisfaction with many economic items this year than they did last year. These items include general quality of life, general standard of living, job satisfaction, job security, current income level, the ability to build assets/wealth, financial security during retirement and job opportunities.

Last year, 45% of rural Nebraskans surveyed were satisfied with their ability to build assets or wealth. That proportion increased to 55% this year.

Similarly, this year, fewer respondents agree with the statement that people are powerless to control their own lives as compared to last year, decreasing from 40% to 32%. Also, most rural Nebraskans surveyed describe their mental health or emotional well-being as good (52%) or excellent (34%). This question has been asked since 2023. The proportion rating their mental health as excellent is higher than it has been the past two years (from 28% and 27% in 2023 and 2024, respectively, to 34% this year).

One occupation class did not share in the increased satisfaction with economic items, or positive reflections of their mental health or emotional well-being. According to the poll, people with production, transportation or warehousing jobs are most likely to be dissatisfied with their ability to build assets or wealth, afford their residence and find job opportunities. They are also most likely to agree that people are powerless to control their own lives and least likely to rate their mental health as excellent.

“The rise in optimism among many rural Nebraskans is encouraging — it shows that when people feel more secure financially, their outlook on life and mental health improve, as well,” Vogt said. “But the data also remind us that not everyone is experiencing that same sense of stability. Understanding these gaps is key to helping all rural Nebraskans share in that sense of optimism.”

When the poll also asked about loneliness, a slight majority of respondents said they hardly ever or never experience feelings of loneliness. Just more than half responded that they hardly ever or never feel: isolated from others (60%); lacking in companionship (58%); and left out (52%).

Comparing these responses by age, the youngest respondents (ages 19 to 29) were more likely than older persons to say they often experience these feelings.

“It’s encouraging that most rural Nebraskans report rarely feeling lonely, but knowing that younger adults are more likely to feel isolated is something communities should pay attention to,” said Mary Emery, professor in the Department of Agricultural Leadership, Education and Communication and director of Rural Prosperity Nebraska, the community development branch of Nebraska Extension. “Strong social ties have long been a hallmark of rural life, yet the poll’s results suggest that younger residents may not be as connected as previous generations.”

However, despite the feeling of loneliness, most rural Nebraskans identify with rural communities — they see themselves as belonging to these communities, identify with people who live there, believe they are typical of people who live there and say their general attitudes are similar to people who live there.

The “Well-being” report and its implications for rural Nebraska will be highlighted during a Rural Poll webinar at noon Oct. 30. Emery will lead the discussion and facilitate the concluding Q&A.

Register here

The 2025 Nebraska Rural Poll marks the 30th year of tracking rural Nebraskans’ perceptions about policy and quality of life, making it the largest and longest-running poll of its kind. This summer, questionnaires were mailed to more than 6,700 Nebraska households, with 943 households from 86 of the state’s 93 counties responding. The poll carries a margin of error of plus-or-minus 3%. Conducted by Rural Prosperity Nebraska with funding from Nebraska Extension, the Rural Poll provides three decades of data on the voices of rural Nebraskans. Current and past reports are available here.